Pandora has released a little burst of data demonstrating that landing on a Pandora station gives an artist more exposure than landing on a terrestrial playlist — when the artist is up-and-coming but not there yet.

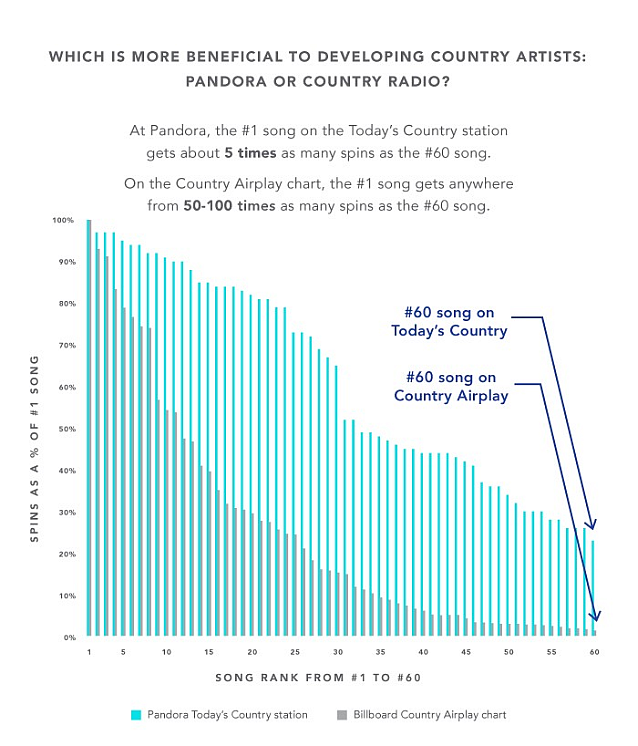

Here’s the data graphic; explanation follows below:

The mini-study compared number of spins for the #60 song on Pandora’s today’s Country playlist, compared to spins for the #60 spot on Billboard’s Country Airplay chart. (This article is by Glenn Peoples, ex-Billboard staff writer who recently took a role in Pandora in Music Insights and Analytics. Oddly, the article was published in Medium, not on one of Pandora’s blogs.)

As the chart shows, there is a wider difference between #1 and #60 in terrestrial spins — there can be 50 to 100 times more for #1 than for #60. In the Pandora playlist, it’s about five times as many, so the #60 artist gets greater exposure.

The point is laid out like this: “Traditional country radio can be very powerful to a handful of stars while Pandora provides more opportunity for a larger number of country artists to get heard.” Glenn Peoples calls personalized online radio “democratic” in this regard.

The article continues with other case studies, where songs had identical or nearly identical rankings in the terrestrial and Pandora playlists. In those examples, the song got more spins in Pandora.

In all this research, Peoples used the total audience tracked by Nielsen for the terrestrial stations, presumably smoothing out the difference between radio’s one-to-many model, and Pandora’s one-to-one model of track spins.

However, Pandora, Spotify, etc do not pay the song writers much.

Broadcast radio pays us 8.5 cents per play.

Open letter to the Music Industry:

As you know, there is a lot of discussion regarding the fair payment

of writers and performers of music

that is being streamed – whether for a very small price per stream or for free.

At Dynamic, where we have many, many recordings available on CD Baby,

we feel that

our income has been adversely affected by the policies in place right

now. A look at our earnings (and therefore the earnings of CD Baby too!)

demonstrates that through the first quarter of 2016, our revenues are

only at 67% of the same quarter last year.

2015 was down slightly from 2015, and I’m guessing that if we had not

added additional titles during 2015, the difference

may have been more significant. If this trend continues through

2016, being down 33% in CD Baby income is not good.

And we’re only one company on CD Baby – if other musicians, record

companies, independent performers, etc. are seeing the

same trend, it’s a serious loss in income to people who are not being

compensated properly for streamed and free music.

We believe CD Baby should unite with the others who have taken a

stand to gain reasonable payment for artistic endeavors.

Spotify payment to Dynamic Recording:

63 streams – $.06 cents. This is a major rip off.

Radio stations pay us 8.5 cents per play.

cdBaby, iTunes, amazon all pay us well.

Smart music buyers love the free music and do not purchase or download.

Many top Artists have pulled there music from streaming, because their sales

and downloads have dried up.

Sincerely,

Dave Kaspersin

President

Dynamic Recording Studio Independent Label

Dave, you are comparing Spotify to terrestrial radio as if it is apples to apples. Spotify is one spin to one listener; radio is one spin to thousands of listeners. You should be thinking about “performances” — impressions on individual listeners. If that one play on radio reached 10,000 people (or 100,000), how much would radio be paying you per performance? (Divide 8.5 cents by 10,000.) Then tell us which is more of a rip-off. As always, thanks for your comment.

Regardless of how you define it, the songwriters are very happy with the deal they get from radio. They are NOT happy with the deal they have with digital media, and have gone to Congress to change it.

“Regardless of how you define it” is a surprising evasion. I am suggesting that Dave Kasperin’s calculation is drastically wrong. If that calculation is the basis of songwriter activism, then I am suggesting the activism is drastically in error. (Perhaps the appeals to Congress have other foundations as well.) In my observation, the mistaken apples-to-apples comparison of online radio to terrestrial radio is a common misunderstanding that plagues musicians. Tim Westergren made a point of this in his recent Midem interview. Musicians have got to think about actual exposure, and stop equating radio spins with online radio spins. They are fundamentally different.

It’s not an evasion. I’m stating a fact. We’re not just talking about musicians, but also the PROs and publishers who are happier with the arrangement they have with radio.

“We’re not just talking about musicians, but also the PROs and publishers…” You are. I’m talking about Dave Kasperin’s calculation in this comment thread. I think Dave is not calculating spins correctly, and might be making the same error I have observed over and over in musician statements. If a misunderstanding of one-to-one spins were the basis of congressional lobbying, it would still be a misunderstanding.

FYI: Dave Kaspersin keeps posting the same information on every article that talks about streaming.

Seems to me this is counter to the intent of the music genome. It sounds like it’s forcing spins of an unknown song on a listener who might not be interested in that song. Is the purpose of Pandora to expose new artists, or to program to the interests of the user? Not all users are interested in new artists.

The research focused on a curated Pandora playlist called “Today’s Country,” not on a user-generated station. The genome governs user-generated stations. Recently, Pandora has put added emphasis on their curated lists, for lean-back music discovery.

Are these curated playlists getting as much usage as the user-generated stations? My understanding is they’re not. So to compare them to an AM-FM station is unfair.

The reason a song is at #60 is it’s not getting much airplay. The reason it’s at #1 is it’s getting a lot of airplay. That’s how the chart works. If the #60 song received more spins, it would be higher in the chart. It seems to be a silly comparison. There are lots of songs at the lower end of the chart by artists who actually ARE stars, like Chris Young and Josh Turner. It’s just that their particular song is getting less airplay than others. And it’s not uncommon to have artists who are not yet stars, like Maren Morris and Chase Bryant, in the Top 10. So the claim is not true.

Our sales and downloads have almost dried up. No one will purchase what they can get for free ! Many major Artists have pulled out of Spotify for that reason.

Spotify is not one spin to one listener. It is simultaneous spins to millions of listeners. We are leaving our Artists on Spotify for now, because when they are finally forced to pay up, it will be a lot of cash, interest and penalties.

Stay TUNED 🙂

I think you’re intentionally playing with words. Every Spotify “spin” or “play” or “stream” that appears on your royalty statement represents one performance to one listener. Yes, there might be simultaneous spins, each one a single performance to a single listener. You know this as a fact; please stop obscuring it. Your 63 spins on radio, paying 8.5 cents each, pays you $5.35. That’s nice until you realize that 63 radio spins might equal 6,300 performances (or many more!), which would pay you $0.0008 per performance. Spotify’s 63 spins paid you $0.0009 per performance. Now imagine that the 63 radio spins reached 1,000 listeners per spin (still pretty modest). That payout for 63,000 performances is $0.00008 per performance. Spotify really starts looking better now. (Please correct any errors I’m making with the math.)

The thing about this is that the PROs, who handle the payments, don’t calculate it using your system. One spin = one performance. That’s how they calculate, and how they certify for performance awards. If you want them to change that, it will take some kind of legal work.

The gist I get is that Dave is trying to compare sales to streaming, which, in my opinion, is like trying to compare apples to oranges.