Tom Webster is Senior Vice President, Strategy and Marketing, at Edison Research, the preeminent media research company addressing how people listen to audio. He is a frequent keynote speaker at podcast and digital audio conferences. This column was originally published in Medium.

Tom Webster is Senior Vice President, Strategy and Marketing, at Edison Research, the preeminent media research company addressing how people listen to audio. He is a frequent keynote speaker at podcast and digital audio conferences. This column was originally published in Medium.

Today I want to dive into some recent data on platforms put out by two Podcast hosting companies (Libsyn and Buzzsprout) and how to think about these kinds of data in the future. There will also be animals.

First, the facts of the case: both hosting companies recently released data on the percentage of their downloads by platform, and there were some sharp differences. According to the excellent reporting on the topic from Podnews, Libsyn reported that Apple accounted for 60% of their April downloads, while Spotify came in a skosh over 13.5%. Meanwhile, their rivals at Buzzsprout also released their April data, and it showed a Very Different Thing: Apple and Spotify tied at around 29%.

James Cridland, the editor of Podnews, did a great job diving into some of the more technical aspects of these data, and concluded that Libsyn was overstating Apple, and Buzzsprout somewhat understating Apple. Do read that. But, as he also states, these technical issues don’t account for the full measure of disparity between the two services. Inside Podcasting reported on the issue, advising that podcasters would do well to question the data they receive from their hosting platforms.

I’ll pose a question that at least some of you may be thinking — why do we care? I’ll give you two reasons: one, as James himself said in the post I linked above, “if Spotify is as big as Apple, that’s big news.” This matters well beyond the posturing of two hosting companies — it cuts to the very changing nature of podcasting itself. After all, if a podcast is a digital audio file delivered via an open standard for automatic downloading, then what we have on Spotify are not podcasts. They are shows. Except Spotify calls them podcasts, the hosts refer to them as podcasts, and the listeners refer to them as podcasts. So guess what: Spotify shows are podcasts.

As I have said before in this space an in others, after 15 years of answering the question our family and friends have often posed — “what’s a podcast?” — do we really want to re-litigate this, now that we have finally made podcasting a household name? Did the Joe Rogan Experience automatically stop being a podcast when it went exclusive to Spotify? Some in the industry would say “yes,” but as far as the listener is concerned, this is a big nothingburger. Just give me my spicy MMA/weed talk, and let’s get on with the show.

The second reason, though, is what I want to spend a little more time on here: the extent to which data like the figures from Libsyn and Buzzsprout disagree says very little about the industry other than two of its hosting companies have very different customers. Libsyn has been around a lot longer than Buzzsprout, in podcasting-dog years, and thus, it is more likely that their body of customers was around and podcasting back when Apple was nearly the only game in town, while Buzzsprout’s comparatively newer hosting customers are more likely to have been indoctrinated from the get-go that podcasting lives in a multi-platform world.

You should also know that Libsyn claims 75,000 shows, and Buzzsprout 100,000. Yes, some percentage of these shows are seemingly or actually inactive. I talked about this at length a few weeks ago in a piece entitled It’s Fun Not To Count Things. But inactive shows “plague” all hosting providers, so let’s set that aside. What I really want you to take away from those numbers is how they compare to the overall number of podcasts extant, as counted diligently by Daniel Lewis on his excellent Podcast Industry Insights page: as of the date of this newsletter, 2,118,515. That means Libsyn speaks for about 3.5% of hosted podcasts, and Buzzsprout 4.7%. Not nothing, surely, but also not enough to characterize an entire medium. You should always remember that when you look at data from hosting platforms.

[A note: James Cridland wrote in to remind me that the figure above for total podcasts is actually total podcasts in the Apple Podcasts directory only, that the actual number of podcasts in existence is much larger, and that he’s discovered some very intriguing things about these numbers that I shan’t spoil. I’ll let the paragraph above stand with this note.]

The podcast industry as a whole is like an elephant in a dark room. Libsyn has a hold of the tail, Buzzsprout a leg. If the lights are off, one could think they are holding on to a mouse, while the other perceives the beast to be a rhino, or a horse, or even a Shar-Pei (which, by the way, are such messed-up animals that they have their own disease, called Shar-Pei fever. Maybe go with a nice Lab, or a Border Collie. WHO’S A GOOD BOI.)

The problem, dear reader, is that the light switch seems to still be off in the room. Unless one entity is counting all of the downloads in the same way, all of this download and hosted data is going to resemble parts of an elephant. Download rankers and host data can only speak to the land they are able to survey. If I listen to an episode of a daily news podcast on Monday in the car, on Tuesday at my desk, and on Wednesday on a long walk, I’m three different people to a download ranker. If I listened on Spotify, I’m three people to a host that counts this data, and no one to a chart that doesn’t. If I listen to the podcast on YouTube, I’m just uncounted, period. The fact that we are talking about the difference between stats from Libsyn and stats from Buzzsprout has nothing to do with their competence in counting those stats. My assumption is they are competent. It has to do with not being able to see the elephant all at once.

The problem, dear reader, is that the light switch seems to still be off in the room. Unless one entity is counting all of the downloads in the same way, all of this download and hosted data is going to resemble parts of an elephant. Download rankers and host data can only speak to the land they are able to survey. If I listen to an episode of a daily news podcast on Monday in the car, on Tuesday at my desk, and on Wednesday on a long walk, I’m three different people to a download ranker. If I listened on Spotify, I’m three people to a host that counts this data, and no one to a chart that doesn’t. If I listen to the podcast on YouTube, I’m just uncounted, period. The fact that we are talking about the difference between stats from Libsyn and stats from Buzzsprout has nothing to do with their competence in counting those stats. My assumption is they are competent. It has to do with not being able to see the elephant all at once.

I want to show you the elephant, all at once.

I don’t have everyone’s downloads/streams/views. I’m not sure anyone ever will. Ad-tech will get us impressions, DR codes and URLs will get us performance marketing metrics, and donations will get us direct support metrics. This ought to be enough for an advertiser. It’s more than you have access to in radio and TV. But comparative data like the platform data released by Libsyn and Buzzsprout is a different dog (and hopefully not a Shar-Pei — again, not a good boi.)

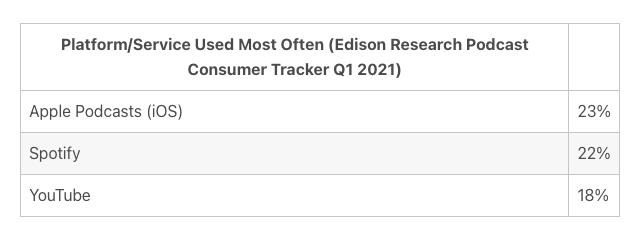

What I do have access to, though, is two years of data from Edison Research’s Podcast Consumer Tracker, and I want to show you some of that data. (I wish I could show you all of it. Really. It costs us a lot to produce in both time and treasure.) It’s not downloads. But it is the only comprehensive measure of the entire podcasting audience and the reach of every producer and platform in the US. In our most recent data (Q1 2021), here is what over 8,000 weekly podcast listeners told us were their top three “services used most often” to listen to podcasts:

This is not a measure of podcasts or downloads. We are not saying that 23% of podcasts are listened to through Apple Podcasts. We are saying that 23% of weekly podcast consumers 18+ in America say Apple is their preferred platform. It is demonstrably true that Apple platform listeners have been listening to podcasts longer than Spotify podcast listeners, and equally true that longtime podcast consumers listen to more shows than people new to the medium, so the relation of this chart to actual downloads may understate the difference between the top two platforms in terms of digital files moved. But the people — the bodies of people who say they prefer these two platforms — these data are about the same. Over the two years we have been tracking these data, Spotify continues to gain ground. This doesn’t mean Apple is losing humans — it simply means more humans are entering the space, and Spotify is bringing them.

This is not a measure of podcasts or downloads. We are not saying that 23% of podcasts are listened to through Apple Podcasts. We are saying that 23% of weekly podcast consumers 18+ in America say Apple is their preferred platform. It is demonstrably true that Apple platform listeners have been listening to podcasts longer than Spotify podcast listeners, and equally true that longtime podcast consumers listen to more shows than people new to the medium, so the relation of this chart to actual downloads may understate the difference between the top two platforms in terms of digital files moved. But the people — the bodies of people who say they prefer these two platforms — these data are about the same. Over the two years we have been tracking these data, Spotify continues to gain ground. This doesn’t mean Apple is losing humans — it simply means more humans are entering the space, and Spotify is bringing them.

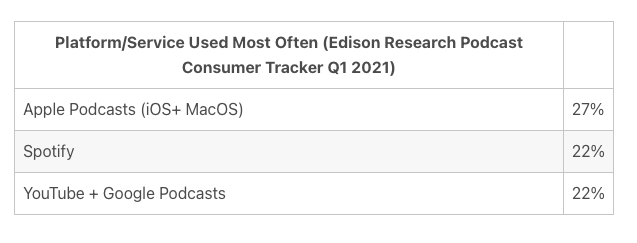

Let’s zoom out one level, and add Apple’s MacOS Podcasts app and Google Podcasts into the equation:

This, from an audience perspective (and not a “counting downloads” perspective) is the Big Three. No one is counting all of #1 except Apple. No one is counting all of #2 except Spotify. And #3? The Great Undiscovered Country.

This, from an audience perspective (and not a “counting downloads” perspective) is the Big Three. No one is counting all of #1 except Apple. No one is counting all of #2 except Spotify. And #3? The Great Undiscovered Country.

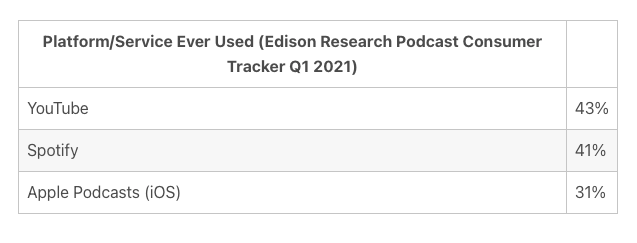

By the way, these data are for the platforms that podcast listeners tell us they use the most — a forced choice. In fact, most podcast listeners use more than one platform to consume podcasts. When we broaden our view one more step to look at all of the platforms that listeners tell us they ever use to listen to podcasts (multiple choices accepted), we get a different ranking:

People who settle into being “a podcast listener” may find themselves attracted to a dedicated platform, like Apple Podcasts, but there is no denying the power of YouTube to find, recommend, and sample content. It is the universal content engine.

People who settle into being “a podcast listener” may find themselves attracted to a dedicated platform, like Apple Podcasts, but there is no denying the power of YouTube to find, recommend, and sample content. It is the universal content engine.

And so we come to podcasting, today: a medium in which two of the top three platforms are not in the business of an open RSS-driven download ecosystem. We’ve covered Elephants and Shar-Peis so far today — let’s round out our journey into the animal kingdom with the humble hedgehog.

What are the skills needed to be a great podcaster, in 2021? Well, some are the same today as they were 15 years ago. Good audio equipment and editing skills. A clear idea. Knowledge of an audience. Consistency. Preparation. These things haven’t changed.

But here’s a new one: a growth mindset. I’m not talking about “I want to grow my podcast.” I assume you want to grow your podcast. I am talking about the ability to continually take in new information, and change your mind, if need be, to act on it. The opposite of a growth mindset, according to Dr. Carol Dweck’s highly influential book Mindset, is a fixed mindset — a mindset that is resistant to change, and one that doubles down on prior beliefs rather than adapt to face a new environment.

Another, even older analogy for this dichotomy comes from the philosopher Isaiah Berlin, who wrote an essay in 1953 called The Hedgehog and the Fox. Berlin maintained that there are two types of thinkers: hedgehogs, who see everything through the lens of a single, inflexible idea or construct, and foxes, who can adapt their thinking to many systems as needed. Berlin took the title of his essay from the Greek poet Archilochus, who wrote, “a fox knows many things, but a hedgehog knows one big thing.” I prefer this way of thinking to Dweck’s “fixed vs. growth” mindset model, because sometimes you need foxes, and sometimes you need hedgehogs. The hedgehog doesn’t have a lot of variety in its approach to life, but if you need to defend yourself from a predator, rolling up into a big spiky ball is pretty darned effective, even if it’s all you got.

Turns out, it’s hard to kill a hedgehog. They tend to die of natural causes, or getting hit by a car, a lot more than they do from being eaten by prey. They aren’t going to move very fast, and they are by no means an apex predator themselves. But they can more than hold their own against knuckleheads like leopards and snakes.

Podcasting is changing. It’s changed. It’s already happened, right under our noses. In the early days of podcasting, it was a time for hedgehogs. We got the basics down. We established some rules and standards, spread the medium largely through word of mouth, and hunkered down while we waited for the audience to come to us. We curled up into big spiky balls. But the data that I showed you here today will challenge you to unroll, let go of fixed ideas, and become a more fluid thinker in podcasting — to embrace the show, not the format.

It’s time to be a fox.

This article was originally published on I Hear Things, my free weekly newsletter on the world of audio, as Elephants, Shar-Peis, and Hedgehogs: What Recent Podcast Platform Data Really Tells Us. I’d love to have you as a subscriber.

.