This column by RAIN guest contributor Mark Mulligan, founder of MIDiA Research, was originally published on LinkedIn. See all his LinkedIn articles HERE.

This column by RAIN guest contributor Mark Mulligan, founder of MIDiA Research, was originally published on LinkedIn. See all his LinkedIn articles HERE.

The music industry is approaching a tipping point, with the building blocks of what will be the post-streaming era beginning to fall into place. The streaming era will make way for something new. Innovation, disruption, and change will define the coming years, with AI, fandom, and the creator economy centre stage. Consumer behaviour will enter a new phase too, having gone from the listening era of the CD, through the consumption era of streaming. What comes next will likely be a polarisation of those two extremes, with participation carving out a path down the middle.

Humans like to think about the history of the world in chapters or eras. The music business is no different. We have had the CD era, the piracy era, and the streaming era. While it is easy to look back and see those changes, it was not as if someone (with the possible exception of Daniel Ek) looked at their calendar on the 7thof October 2008 and said “oh, we are now in the streaming era”. We need to look for early warning signs to try to understand when change is coming. The music industry is full of them right now and the change to come will likely be so fast that music licensing will need a new playbook. Rights normally play catch up to new tech, but this next wave of change threatens to run far faster than rights can.

Technology’s exceptionalism

A recurring theme in the history of rights is rightsholders translating and transposing traditional frameworks into digital contexts, while trying to grapple with how things change when technology does something instead of a human. For example, when someone sings a song on a livestream to an audience of 20 people, that is considered in an entirely different context to someone singing to 20 people in their local bar. Similarly, if someone was to spend weeks learning every chord progression and melody of an artist to write a song in their style, there would be no rights permutations unless the resulting work actually replicated the music of the artist, as opposed to the style. But get a machine to do the learning and suddenly there is a (contentious) rights conversation to be had.

This is because technology can do the input stage once but the output an infinite number of times. The 20 people on the livestream could suddenly become 200,000. The music learning could be used by millions of people, not one. This approach has enabled music rights to be both protected and remunerated, but it has also led to incongruous work arounds. This is happening even in streaming, where there is both a mechanical right and a public performance right, because a stream is simultaneously considered a copy and a performance. In practice, it is just a stream.

The music world has changed and so will music rights

The reason music rightsholders were able, to put it bluntly, to shape the streaming market in their image is because the majors had a de-facto monopoly over supply of content (Amazon was the only global streaming service that was able to launch without all three majors on board). Streaming services had to curb their enthusiasm and make their propositions fit rightsholders requirements (both in terms of rights and cold hard cash).

What comes next will not play out that way because:

- Major labels’ market share has lessened

- Cultural fragmentation means mainstream is less important (you do not necessarily need the hits anymore)

- Future music experiences will be less focused on traditional recordings

So, if music rightsholders were to lock themselves in another long-term debate about whether something is a copy or a performance or both, the market will likely work out a way to progress without them. What is more, many of the rights that will be implicated or created in this new era — such as the right to an artist’s voice (not the recording of it) — belong to the artist, not the label (or at least not yet, as labels should and probably will try to write these rights into future contracts).

To be clear, this is 100% not an advocation of avoiding rights – quite the opposite in fact. If the compositional rights side of streaming had just been a new streaming right, there is no inherent reason why songwriters would have got paid a penny less. The simpler and more streamlined music rights can be for future formats, the more likely that more of the resulting revenue will result in royalty payments.

When they were licensing streaming, rightsholders could threaten to throw up a roadblock. In this new world, they will only be able to throw up speed bumps.

AI will accelerate change

The path to a vibrant and licensed music future will require a more agile and future-facing approach to music rights. The technology we have in place today is already throwing up rights questions that are not easily answered. The rate of change is going to accelerate due to the role of AI, less in terms of the apps created and more because of how AI itself will accelerate learning and development. Look no further than the AI programme that generated 40,000 new bioweapons in just six hours. AI is going to power a new industrial revolution process that will likely leave today’s tech landscape looking like the agrarian economy that the first industrial revolution rendered obsolete.

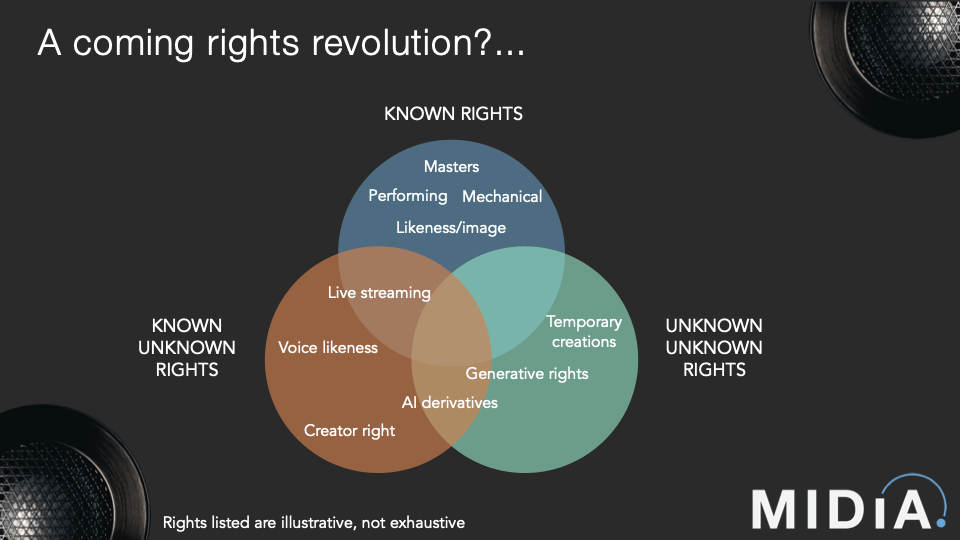

So, how do we plot a path forward? For that, I am going to turn to Donald Rumsfeld’s ‘known unknowns framework’, or the ‘Rumsfeld Matrix’ as some like to call it. For those of you too young to remember it, this is what I am talking about. Basically, it is a framework for splitting the world into what you know (known knowns), what you know you do not know (known unknowns), and what you do not know you do not know (unknown unknowns). It translates really well to music rights.

The known unknown rights are those we either already know we need or that there is the start of a conversation around (e.g., live streaming is hardly new, yet we still lack a global licensing solution). The unknown unknown rights are all the new possibilities merging technologies may throw up. Here are two key examples:

1. Temporary rights: Much of the social world is defined by content that only exists for a limited time (e.g., Instagram Stories lasting for just 24 hours). It is reasonable to assume that much of the music content consumers will create in the future will also only be temporary, but revenue will still likely be generated against them. So, unless a rights framework exists, the creators (consumers in this context) would not be renumerated for their creation.

2. Generative rights: Most of the rights conversation around generative AI has focused on the works that AI learns from being protected and remunerated. But that is only the input. There is also the output. Just like De La Soul, that spent years clearing samples to get onto streaming, still own the rights to their songs, the creators (and consumer creators) that use AI to generate music will have created a work that should have a right of its own. Years spent clearing source rights will not work. So, the generative AI right will likely need to incorporate some form of derivative rights to ensure money flows to the rightsholders. AI start-up Boomy somewhat cynically claims the rights to all works created by users on its platform but has, perhaps inadvertently, established the precedent for a generative creation right.

None of this will be easy. But little will be easy about what comes next. If you thought change was fast this last decade, wait for the next one.

As William Gibson’s quote goes: “The future is already here – It’s just not evenly distributed.”

————

.