This guest column was originally published on A Journal of Musical Things.

This guest column was originally published on A Journal of Musical Things.

Last month, much to my shock and surprise, the calendar told me that I’d been in the radio industry for 35 years. The anniversary gave me pause for reflection. I started looking back on the stations where I worked, the places I’ve lived, the people I’ve met and how the industry has changed during those decades.

While AM and FM are going to be with us for a long time yet, today’s tech–everything that goes into sending out those signals–has changed dramatically. Yes, radio still involves people sitting in a studio speaking into a microphone, but the way radio folk work, the tools at their disposal and the way we interact with our listeners bear little resemblance to what was standard operating procedure when I first started.

Let me show you what I mean. What follows are some personal recollections and experiences with how radio (and the music it plays) has been affected by technology over last three-and-a-half decades.

The Vinyl-and-Cart Days

Because I’m some kind of idiot savant for dates, I know that that the first time I a microphone in the studio of a commercial radio station was at 3:04:20 pm on Saturday, November 14, 1981, right after the top-of-the-hour Broadcast News report. The station was CFQX-FM, a brand new independent station in Selkirk, Manitoba. And at the risk of sound like Ted Baxter, it was a 7,000-watt station in the middle of a wheat field down the street from the Manitoba Mental Health Centre. We had ten full-time staffers and five part-timers.

The station had a crappy place on the dial (92.9 Mhz; the station relocated to 104.1 Mhz in 1987, a year after it flipped from elevator music to country) and the temperamental transmitter was a used unit bought from the University of Manitoba when they shut down their campus station. The station had zero ratings and plunged into bankruptcy less than two years after signing on. But I’m forever grateful for Denis Cloutier–the always rolling-his-own original owner–for giving my start in the business.

(I seemed to have stumped Google when it comes to searching for images from those days. I’m sure I have pictures somewhere in my basement, but I have no idea where to begin.)

The main studio was pretty basic: a couple of turntables (Technics SL-1200s) for playing LPs and 45s, a custom-made console with old-school rotary pots (never seen one since), a set of speakers, one of these Sennheiser microphones and a three-slot ITC cart machine.

The ITC unit was used for playing carts, an ancestor of the 8-track tape.

Typical Fidelipac carts

Carts–self-contained loops of tape–were used for commercials, promos, jingles and news clips. AM stations (and some FMs) also dubbed all their music onto carts. Once the audio on the cart finished playing, the tape kept running until the machine read an inaudible tone that marked the beginning of the audio. Some machines required that the operator manually started each cart once the previous one finished while others were set up to fire carts in sequential order automatically.

Carts could be very annoying. They jammed. Machines misread cues points. And operators had to create a giant stack of these things for each hour according to a printed commercial log. Woe to any announcer who (a) missed a spot; (b) played a spot in the wrong place; or (c) failed to note on the log the exact time each commercial was played. NO excuses. (There was one shift at CJRL 1220–my second station and first full-time job–in Kenora, Ontario, before Labour Day when 63 minutes worth of commercials were scheduled for the 8am hour. When I explained this to the person who scheduled the spots, she said “I don’t care! They have to be played!”)

Playing music had its own routines, rituals and challenges. Records had to be pulled from the library and played in a specific order. Each record needed to be individually cued up and manually mixed with the next selection. The artist and title needed to be written out down the music log, carefully paying attention that Cancon levels were correct. And at the end of the shift, all the records needed to be filed back into the library. Again, woe to any announcer who screwed up.

Songs were written out on different coloured recipe cards, the colours denoting different categories of songs. Announcers were instructed to play the song on the card at the front and then file it at the back. That’s how rotations were determined. And woe to any announcer who cheated by skipping cards.

As the records played, we were expected to answer the request line, which was constantly ringing. Once an hour, we’d had to run down the hall to the newsroom where a printer continuously spewed out metre after metre of printouts: news, sports, weather, bulletins, all in BLOCK CAPS. Some stations insisted that announces rip the printouts story-by-story, stacking them by content. And if we had to go to the bathroom, you had to wait until a song of sufficient length came up. Wanna know why so many DJs loved Don McLean’s “American Pie” or “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” from Gordon Lightfoot?

The phone rang constantly with people demanding requests or reporting local sports scores, all of which had to be recorded for the newsroom. And because Kenora was in the middle of nowhere, many of its listeners didn’t have telephones. People knew to tune in at specific times of the day for Contact, where messages were read out to those without normal means of communication. (Contact messages also came in by the dozens over the request line. All of them had to be noted and filed for the next report.)

Once I finished my shift, I was expected to do record and produce new commercials. I’d read the script onto a reel-to-reel tape, find some background music from a library of 30- and 60-second clips on the station’s library of production material, mix the two together and then dub everything onto cart. And woe to any announcer who did not complete their production duties.

Computers? There were none. Everything was done manually, either in longhand or with typewriters. All radio work was very manual and very labour-intensive.

Computers and CDs Appear

By the time I got to my third career stop at KX-96 in Brandon, Manitoba, in the fall of 1983, we’d begun to hear about this new thing called the “compact disc.” At first, there were too few discs to replace vinyl records so playing any CD was treated as a special thing. For example, we had a show called “Laser Tracks” Saturday nights at 11 where we’d play an entire CD to highlight its superior sonic quality. And since discs were so expensive, we borrowed each week’s disc from the local stereo shop that sponsored the show.

The first computer I ever saw at a radio station was this Olivetti M24 in the sales department of Q94-FM/Winnipeg (station number four) in the summer of 1984.

Frankly, it was pretty useless. With no hard drive, you had to load the OS on a 5 1/4 inch floppy before it could do anything. I think it ran a form of DOS, but I couldn’t figure out how it worked or why we even bothered buying one. It sat alone on its own little stand in the middle of sales pit. I never saw anyone use it.

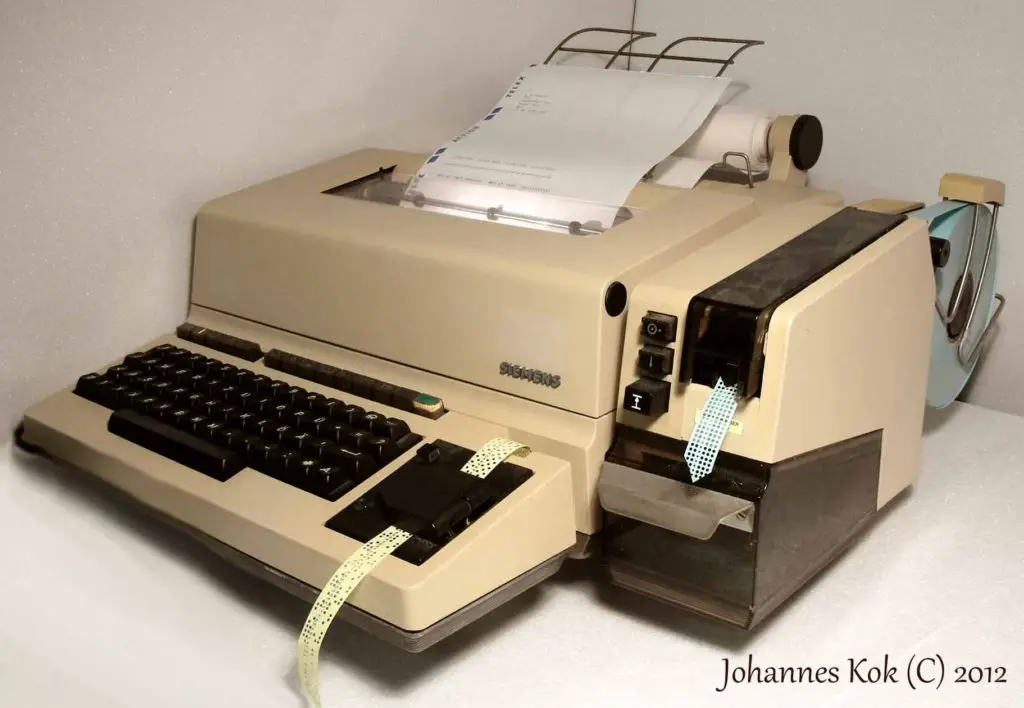

When I got the job as music director, it was my job to report all the changes to our playlist to RPM magazine in Toronto. I could either call them (frowned upon because the station was stingy with when it came to long-distance charges) or use the station’s Telex machine. It involved transforming printed text into a strip of paper with holes punched into it. You’d then feed that strip into a reader, which would then transmit the data.

As for the control rooms at KX-96 and Q-94 FM, things hadn’t changed at all. It was all still a vinyl-and-carts world documented and directed by paper logs. We spent long hours answering the request lines.

CDs Go Mainstream

I arrived CFNY-FM on October 3, 1986, and was immediately confronted by three giant Studer CD machines…

…mounted above three Technics studio turntables with separately-mounted tonearms.

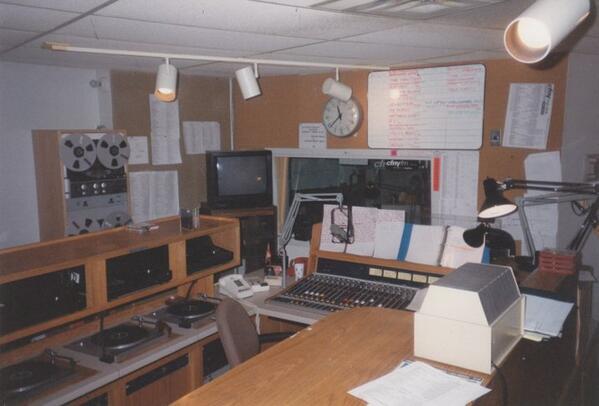

Here’s a picture I took of the control room. The barn-like thing on the right side of the photo is an ionic air cleaner. Announcers were still allowed to smoke in the studio back then.

This is a shot of me in the old CFNY studios at 83 Kennedy Road South in Brampton, Ontario, in the spring of 1989. The console was made by McCurdy (I think), just like the boards in Kenora, Brandon and Winnipeg.

By 1993, the majority of the music we played at CFNY was from compact disc. The Studers were eventually replaced with these cash register-like Technics SLP-1200 units. (They were introduced as the CD equivalent as the SL-1200 turntable–and they were like tanks.)

Several other technological developments arrived. The sales and traffic department had a computer which connected to a printer the size of a chest freezer. The music department acquired their own machine which ran a simple music scheduling program. Music logs were printed out using a noisy dot-matrix printer. And then there was the fax machine. Being able to transmit scribbles on pieces of paper through phone lines was viewed upon as a sci-fi level miracle. Soon requests and other announcer correspondence were flowing through the machine in reception. This was the first innovation in announcer-listener interaction since the telephone.

Meanwhile, the engineers were playing with a new toy: a machine that recorded CDs.

I seem to recall the machine costing $12,000 and each blank disc running about $40 each. And the recorder’s speed maxed out at 1x. Yes, it could only burn discs in real time.

Everything else in the building was the same as it ever was. Commercials and jingles on carts. Production done on magnetic tape. Endless picking and filing of vinyl and CDs.

Computers Arrive

More computers started arriving at the station around 1993. I first began writing Ongoing History programs on an underpowered 286 machine running a Symantec word processing and database program called Q&A. Other 286 machines were employed in the music department and on the desk of the sales assistant. The traffic department–the people who scheduled the all-important–still had their own unit connected to that freezer-sized printer. It was so noisy that it was given its own room.

By the end of the 90s, a new hard drive-based playback system had been installed. Called DCS, it was DOS-based and eliminated the need for carts. All commercials, promos and jingles were loaded into the system and automatically logged when they were played. But because the system could be finicky, announcers had to confirm the spots ran as scheduled by marking down the times the commercials ran on a paper log. Redundancy was the name of the game. Over a period of months, songs were loaded into the system (initially using the MP2 [sic] format), eliminating the requirement for vinyl and CDs.

We were amazed at the server which used four 9GB SCSI hard drives. “THIRTY-SIX GIGABYTES OF STORAGE? WOW!” But this came at a price to our egos. Essentially, announcers interaction with music and commercials had been reduced to making sure a series of elements played as scheduled. And everything was no longer scheduled by the DJ but by someone else in the building. DCS could be set up to even mix the songs. In other words, it was like a suped-up iTunes player.

The other big news was the arrival of something called “the Internet.” At first–this would be 1995–management wasn’t interested in this nerdy fad, but the staff kept after them until we launched a cooperative venture with an early Toronto-area ISP called Passport, who created our first Mosaic browser. Our first URL was www.edge.passport.ca. This screenshot is from 1996.

Now here’s a screenshot from 1999.

This heralded the arrival of email. It came slowly at first, but once a computer was installed for announcer use in the control room, the dribble became a flood. In time, it became a requirement that announcers answered the request line, collected faxes and dealt with email. But since DCS was taking care of the music and commercials, the Powers-That-Be insisted that DJs had all kinds of extra time to do other things. “We’re not paying you just to sit around!”

Computers began to appear on everyone’s desks and everyone’s studio. The old 286s were replaced by 386s, 486s and Pentiums. Networks were installed. Engineering departments hired dedicated computer people. And production studios evolved from using magnetic tape to using digital audio workstations running software like Pro Tools. Reel-to-reel machines were junked. Everything became digital.

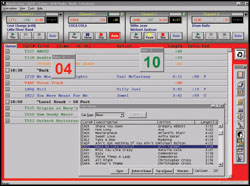

On-air playback systems evolved, taking the radio studio deeper into the digital realm. The next step for us was a Windows-based software called Maestro.

In addition to being able to play back any sort of audio you might need in a radio studio, Maestro also had the ability to work 100% independently without any kind of announcer intervention. This was the real beginning of voice tracking and the elimination of live announcers overnight, on weekends and on holidays. Why should management pay for live bodies when a computer could handle the job? Today automation is rife across the industry in markets of all sizes. This (in my opinion, anyway) has irreparably harmed the development of new announcers since they have fewer places to pay their dues. Even a rookie DJ is more expensive than a computer running Maestro (or Scott or MediaTouch or whatever) on auto.

Social Media, Apps and Mobile Phones

Today’s playback systems are very robust. Crashes–something that plagued DCS and the versions of Maestro I had to use–are rare. Automation modes are far more sophisticated, too. Even when there’s a live announcer in the chair, the software handles almost all the heavy lifting. Announcers follow their logs (most radio stations now merge their commercial and music logs into one), wait for their scheduled talk breaks, do their thing and then hand things back over to the machine.

Between those times when the machine beckons them to talk, announcers answer the request lines, answer texts, tweet (and respond to tweets), post blogs to the station’s website, post to Facebook, deal with comments, monitor the station’s Instagram account and surf the Internet for the material they can use for their next talk break. And because people can now stream a radio’s signal online through its website or an app, we now get feedback from listeners all over the world.

Meanwhile, any station that doesn’t have an online department or someone monitoring social media is hopelessly behind the curve. Once a big deal to have one nerd looking after the website, stations have multiple people creating content, advertising and contesting as well as conducting all kinds of audience research.

What’s Next?

Like I said at the outset, AM and FM are going to be with us for a while yet. The medium remains popular (more than 90% of our population listens to radio every week), profitable (although with margins smaller than they used to be) and powerful (ask advertisers and record labels how effective radio is). But there are developments on the tech front that industry is watching very closely.

Analogue vs. Digital: AM and FM signals work well, but have their physical limitations. Countries such as Norway are moving towards shutting down all FM transmitters in the country by the end of 2017, moving entirely to Digital Audio Broadcasting. Britain, most of Europe, China and Australia have either adopted DAB or are conducting trials. (Canada tried and abandoned DAB; the US rejected it outright in favour of HD Radio.) Both systems require that consumers acquire new DAB or HD Radio radios. How will things shake out in the marketplace?

IP Delivery: Could terrestrial stations start broadcasting via the Internet instead of AM and FM? Maybe. But given that there are tens of billions of radio in use, Internet-only radio stations probably are still a ways off.

Streaming: How does radio compete in a world where each person with an Internet connection can have instant access to 35 million songs?

The Connected Car: Since the 1930s, radio has enjoyed supremacy in the car. What happens when a critical mass of people begin using their mobile phones and the advanced infotainment systems in their vehicles? How can radio hold onto is in-car audience?

Self-Driving Cars: If people in the vehicle no longer have to keep their eyes on the road, what distractions/entertainment other than radio will they turn to?

Talent Issues: It’s becoming increasing difficult to find top-notch on-air talent. With a farm system of smaller stations decimated by voice tracking, where do young announcers go to learn their craft?

Interactivity: Unlike other entertainment media, AM and FM signals are one-way. Any interactivity with a station has to be conducted via another medium like email, texts or social media. There are some options–NextRadio looks very promising–but the industry really needs wireless providers to turn on the FM chips inside virtually every smartphone on the planet.

Media Habits of Young Generations: Unlike previous generations, today’s young people have never known a world without the Internet or always-on connectivity with…well, everything on the planet. Terrestrial radio needs to figure out how to meet the needs of the next generations of listeners.

Whatever happens, I want to be a part of it for as long as possible. I’ve been in radio for more than half my life and I’m not about to quit now.

“where do young announcers go to learn their craft?”

Wherever they can. You’d be surprised. I heard of a college that turned over its FM station to professionals, and so the students started an LPFM on their own. They start their own internet stations. I just got an email from a student at a college who was hired to do a part time shift at a local FM station, and she now wants to pursue radio as a career. She’s 22. I get messages like this every day. They want to learn. They want to work. We who are in the business need to listen to them, seek them out, and put them to work NOW.